How can I find a meteorite?

You’ve read the books, combed the Internet and watched countless meteorite programs on TV.

You know exactly what to look for, and you’re ready to go on your first meteorite hunt, right?

Think again!

Almost every person who contacts the Center for Meteorite Studies about a potential meteorite describes their find as “heavy and magnetic, with a shiny, black fusion crust and flow marks from melting”.

Have they all found meteorites? No. In fact, over 90% of these people have found terrestrial rocks covered in desert varnish, slag or iron ores such as magnetite and/or hematite (fewer than 1% of rocks sent in to the Center are actually meteorites).

Isn’t it true that all meteorites are highly magnetic and won’t mark a streak plate?

No. While it's true that freshly-fallen meteorites are usually magnetic and won't mark a streak plate, the most common cold finds are weathered ordinary chondrites, which are often only weakly magnetic because of the oxidation (rusting) of the iron they contain. Because of that oxidation, they’ll leave a brownish-orange streak on an unfinished piece of ceramic (see below for description and photo).

The most common magnetic “meteorwrong” that won’t mark a streak plate is slag (see below for photos and description). Magnetite, though highly magnetic, will leave a grey streak, and hematite (often occurs with magnetite) will streak reddish-brown (see below for streak photo and mineral descriptions).

Plainview, an ordinary chondrite from Texas, USA. The exterior of this complete specimen of Plainview is typical for stony meteorite finds. The specimen measures ~19 cm at its longest point. Photo © ASU/CMS.

Don't all meteorites have a shiny, black fusion crust?

Most people, when starting to search for meteorites, have only seen photos of freshly-fallen meteorites with pristine black fusion crusts (definition below). The longer a meteorite has been on Earth, however, the more the fusion crust wears away, leaving the meteorite a rusty brown color. This process is accelerated in humid areas and regions that receive large amounts of precipitation.

I found a rock in the desert with a black coating – does that mean it must be a meteorite?

No. Actually, what you think is fusion crust may be desert varnish. Desert varnish is made up of organic material, manganese and iron oxides, and clay minerals and forms a shiny, black coating on the surface of rocks in dry environments. Because this coating can form on a number of different rock types, some desert-varnished rocks can be magnetic, making it easier to confuse them with meteorites.

Terminology

Weathered ordinary chondrite

A weathered ordinary chondrite is a stony meteorite that has been exposed to the elements on Earth's surface for an extended period of time. These meteorites are heavily oxidized, and are often only weakly magnetic, with a rusty brown exterior.

Meteorite falls vs. finds

A "fall" is a meteorite that was observed as it fell, and then collected. A "find" is a meteorite that was not observed to fall but that was later recognized by distinct features and collected. A “cold find” is a meteorite find in an area where meteorites have not previously been recovered or observed.

Fusion crust

Fusion crust is a layer that forms on the outer surface of a meteorite as the result of frictional heating and abrasion as the meteorite enters the Earth’s atmosphere. Freshly-fallen meteorites usually have a shiny, black fusion crust. The longer the meteorite remains on Earth, however, the more the fusion crust wears away; the surface of weathered ordinary chondrites is often a rusty brown color.

Streak test

A streak test involves scratching a sample across an unglazed ceramic tile to see if it leaves a mark. While freshly-fallen meteorites won’t mark a streak plate, the overwhelming majority of meteorite finds are weathered ordinary chondrites, which may streak brownish-orange.

Hematite leaves a red-brown streak and magnetite leaves a gray-black streak. Other minerals may leave brown, black, green-black, gray, or even yellow streaks.

If your specimen does not leave a streak, you may have a piece of slag: a man-made industrial byproduct of the mining and metallurgy industries.

Streak plate showing magnetite with gray streak (left) and hematite with reddish-brown streak (right). Photo © ASU/CMS.

Return to top

Magnetite and hematite

Two common meteorwrongs are the iron oxide minerals hematite (Fe₂O₃) and magnetite (Fe₃O₄). They occur quite commonly throughout Arizona and the United States, and are actively mined as iron ores. You may have seen jewelry made from shiny, black hematite beads, or driven past a sign for “Magnetic Hill”; a common local place name for large deposits of magnetite.

Hematite with magnetite. Photo © ASU/CMS.

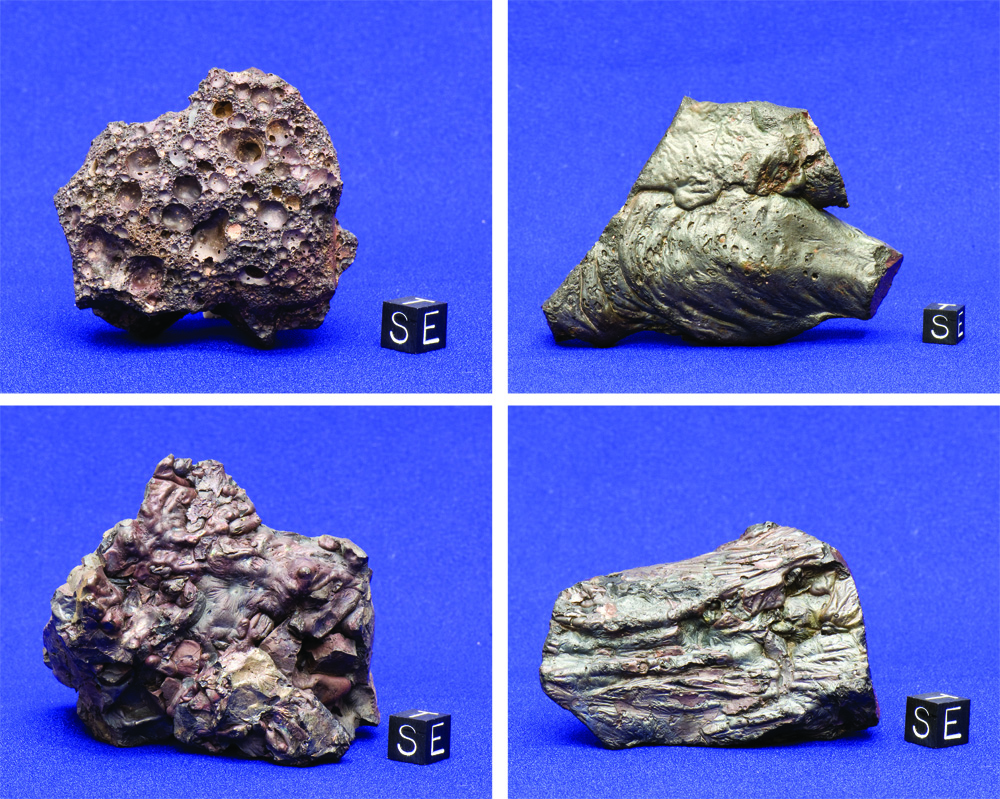

Slag

Slag, a man-made byproduct of mining and metallurgy, is often made up of metal, sometimes combined with metal oxides and/or sulfides, and many additional components (silica, calcium, etc.).

Because slag is formed by the cooling of melted industrial byproducts, it often displays melt texture, such as flow marks and vesicles (holes or "bubbles" in the surface where trapped gas has escaped during cooling) and can be heavy and magnetic. It may even appear similar to some meteorites, so be wary of this meteorite impostor!

Slag can be found almost anywhere, even in what might be considered “the middle of nowhere”, because it is commonly used for fill in roads or train tracks. This is especially true in states like Arizona, where a rich mining history extends back hundreds of years.

Different examples of slag. Photo © ASU/CMS.