Size

Meteorites vary in size from a few millimetres across to several feet in diameter. The largest known individual meteorite, Hoba (iron, Namibia), is shown here with a collection of tiny Holbrook (chondrite, Arizona) specimens. Hoba measures just under 9 feet (2.7 metres) wide, while the Holbrook pieces measure up to 1 centimetre (1 inch = 2.5 centimetres).

|

|

| Holbrook. Photo: L. Garvie/BCMS | Hoba. Image credit: Eugen Zibisco |

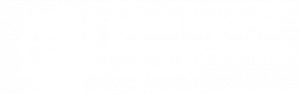

Shape

Meteorites are rarely round in shape. They are typically irregular, with rounded edges.

|

|

|

L’Aigle; chondrite. Photo © ASU/BCMS.

|

Petersburg, eucrite. Photo © ASU/BCMS.

|

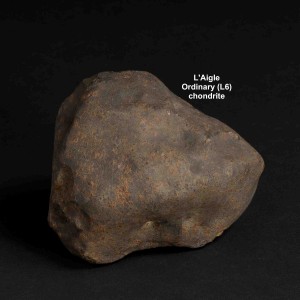

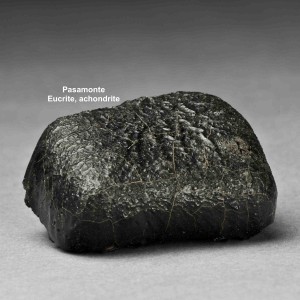

Color

The surface of a freshly fallen meteorite will appear black and shiny due to the presence of a “fusion crust,” the result of frictional heating and abrasion (or ablation) of the outer surface of the rock as it passes through the Earth’s atmosphere (see Pasamonte, below). The longer a meteorite has been on Earth, however, the more the fusion crust wears away, leaving the meteorite a rusty brown color (see Canyon Diablo, below).

|

|

| Pasamonte, eucrite. Photo © ASU/BCMS. | Canyon Diablo, iron. Photo © ASU/BCMS. |

Surface

While most meteorites have a smooth surface with no holes, some meteorites exhibit thin flow lines or thumbprint-like features called regmaglypts. Flow lines are cooled streaks of once-molten fusion crust. Regmaglypts are likely caused by the severe melting and abrasion of the components of the meteorite as it enters the Earth’s atmosphere.

|

|

| Krähenberg, chondrite. Photo LoKiLeCh. | Close-up of Bruno, iron. Photo © ASU/BCMS. |

Weight

In general, meteorites are heavier than Earth rocks of the same size because they have a higher nickel-iron content. Naturally-occurring Earth rocks are usually poor in metals, particularly nickel, in comparison to meteorites. The softball-sized iron meteorite (Losttown) on the left weighs over 5.5 pounds, while the large, regmaglypted iron on the right (Henbury) weighs over 282 pounds, and is under 24 inches long at its widest point!

|

|

| Losttown, iron. Photo © ASU/BCMS. | Henbury, iron. Photo © ASU/BCMS. |

Interior

Most stony meteorites, especially ordinary chondrites (the most common type of meteorite recovered on Earth) will exhibit tiny metallic flecks on a broken, cut, or polished surface. In addition, most stony meteorites will exhibit small round chondrules. This section of Mezö-Madaras measures ~4 inches.

|

| Mezö-Madaras, chondrite. Photo © ASU/BCMS. |

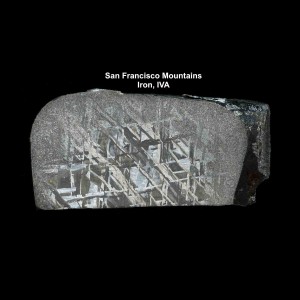

As their name implies, iron meteorites consist almost entirely of metal. The distinctive Widmanstätten pattern (named for Count Alois von Beckh Widmanstätten, director of the Austrian Imperial Porcelain Works, in 1808), seen on some etched iron meteorite surfaces, is created by the interlocking crystal structure of two nickel-iron alloys (kamacite and taenite).

|

|

| Muonionalusta, iron. Photo © ASU/BCMS. | San Francisco Mountains, iron. Photo ASU/BCMS |

Stony-iron meteorites contain approximately 50% silicate and 50% metal which, in some pallasites, may show Widmanstätten lines after etching.

|

|

| Seymchan, pallasite. Photo © ASU/BCMS. | Hainholz, mesosiderite. Photo © ASU/BCMS. |

Magnetism

A magnet will be attracted to most meteorites, even stony meteorites, due to their high iron and nickel content.