Bringing the Moon to Arizona

To celebrate of 60 years of the Center for Meteorite Studies, we’re posting stories of historical Center events, new research initiatives, exciting outreach programs, conservation and growth of the Center’s invaluable meteorite collection. We invite you to follow us on social media, and share your memories and photos of the Center for Meteorite Studies using #CMS60.

As implied by its name, research at the Center for Meteorite Studies focuses in large part on meteorites, most of which originated on asteroids. However, the Center also supports research on other Solar System bodies such as the Sun, Moon and Mars. The practice of working on planetary samples other than meteorites was established in the early history of the Center when Founding Director Carleton Moore was among the handful of scientists in the world selected to analyze Moon samples returned by the Apollo missions.

The seeds of Moore’s Apollo analyses were planted years before the Moon landings. As newly-appointed Director of CMS, Moore attended a conference of meteorite curators in England in 1962. There, metallurgist Howard Axon suggested that carbon contents of meteorites should be studied, as theoretical work on iron and steel carried out by metallurgists could benefit from carbon values from meteorites.

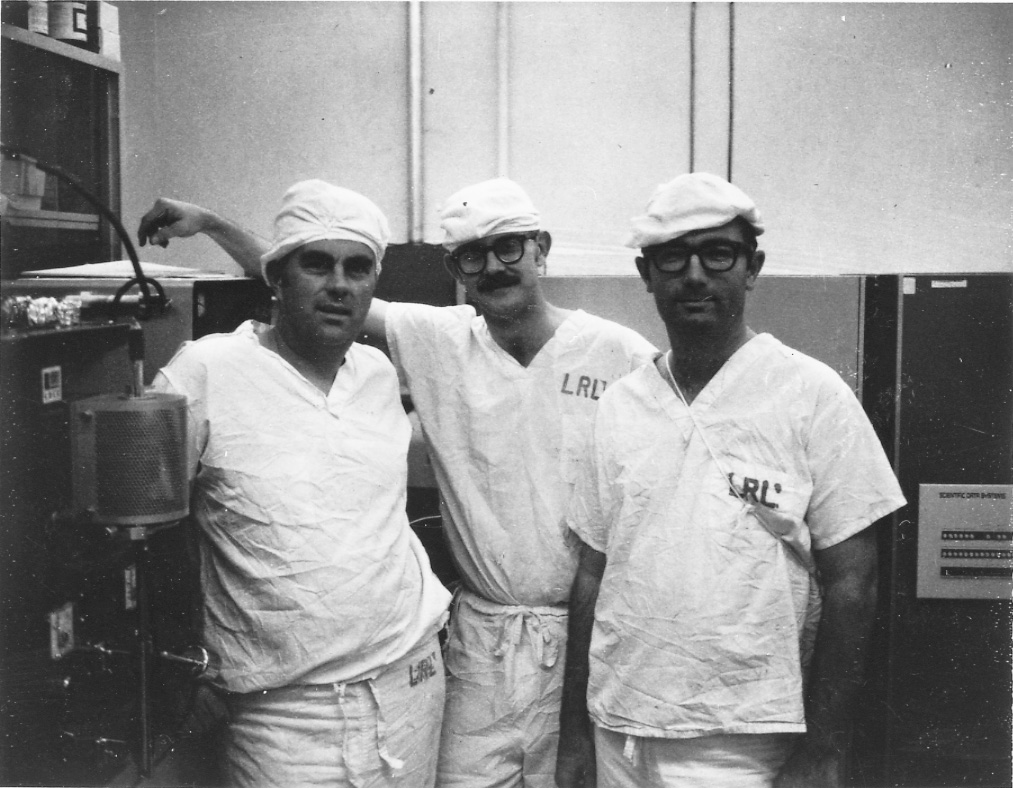

Inspired by the suggestion, Moore obtained a state-of-the-art LECO carbon analyzer, which operated by combusting a sample and then analyzing the resulting products by gas chromatography. Moore and CMS Curator Charles Lewis began by analyzing carbon in iron meteorites and, once they successfully demonstrated the technique, they moved onto analyzing a wide variety of chondrite meteorites. The expertise developed with carbon enabled Moore, Lewis and the increasing numbers of undergraduate and graduate researchers in the CMS to move onto the characterization of other volatiles in meteorites including nitrogen and sulfur. Their work resulted in numerous publications and established the reputation of the CMS in studies of volatile elements in meteorites

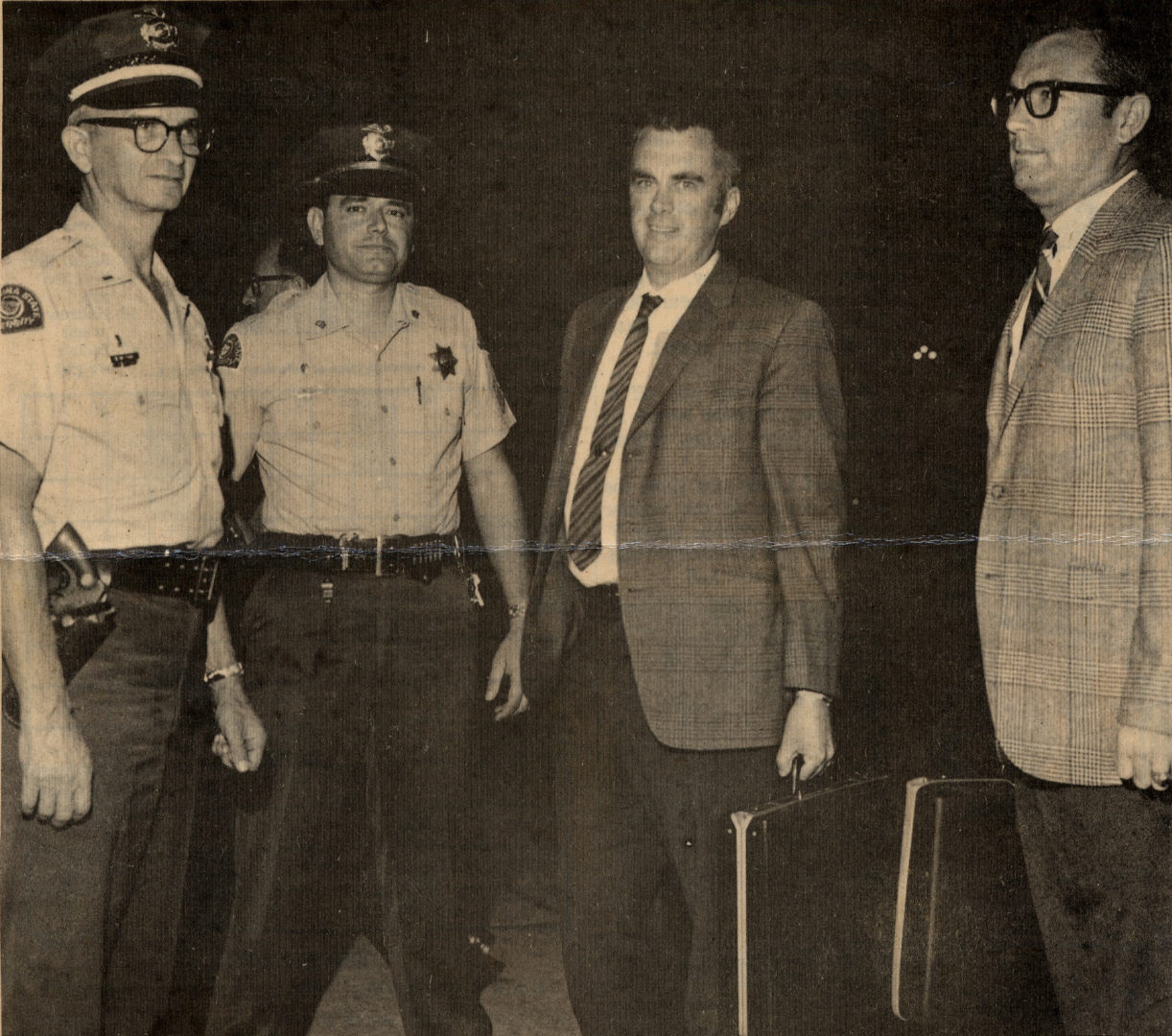

Prior to the first Moon landing, Moore’s successful meteorite analyses helped earn him a grant from NASA to analyze carbon in the samples returned by the first lunar landing mission, Apollo 11. This work was independent of the Lunar Sample Preliminary Examination Team (LSPET), the team of scientists assigned to analyze the samples in the Lunar Receiving Laboratory (LRL) at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC; now known as Johnson Spaceflight Center) immediately upon return of the lunar samples to Earth. However, when carbon analyses of the Apollo 11 samples by the LSPET were unsuccessful, Robin Brett, a NASA geochemist in charge of science at the MSC, brought Moore onto the LSPET immediately to get the needed carbon data. Because the CMS was the only facility with the analytical machinery in place for proven carbon analyses, Moore flew to Houston to pick up the Apollo 11 samples and brought them back to ASU for analysis.

As the Apollo 11 analyses were underway at the CMS, the rapidly approaching launch of Apollo 12 compelled Moore to work quickly to recreate the analytical setup from the CMS at the LRL so that his future LSPET analyses could be done in Houston. The samples that the LSPET were charged with analyzing were chosen by the curatorial staff at the MSC after they cataloged the samples returned by each mission. When an important sample or suite of samples was identified, it was released to the LSPET members for analysis. The cataloging and release process could take months; thus, some LSPET members would stay in Houston until all the preliminary analyses were completed for a mission’s samples. Rather than follow this model, Moore traveled to Houston for each sample release, leaving on a Friday night and returning on a Sunday night so as not to affect his Center directorship and teaching duties. After Apollo 14, the lunar samples were no longer deemed a potential biological hazard because the likelihood of lunar organics or life forms was eliminated by analyses of the Apollo 11, 12 and 14 samples. Moore and his team could then carry out the carbon analyses for LSPET on the Apollo 15, 16 and 17 samples at ASU.

Security around the lunar samples was understandably tight. The Apollo 15, 16 and 17 samples and other samples Moore was authorized to analyze through his own grants were mailed from the MSC but Moore had to pick them up directly from the post office. Once at ASU, the samples were kept in a cabinet secured with two locks from a single vendor designated by NASA. The lock did not come with a set combination. Moore was required to set the combination himself so that he would be the only one capable of opening the lock. NASA also required that the samples be checked by law enforcement personnel twice a day so that in the event the samples went missing, the time of disappearance would be tightly constrained. During late nights of work by Moore and his students, though, they often found that the nighttime sample check was not done. Fortunately, additional security for the cabinet was provided as only the Center could. Moore kept heavy iron meteorites in the base of the storage cabinet to ensure it could not be moved.

Moore and the CMS team ultimately analyzed over 200 lunar samples. These analyses, along with discussions with ASU Department of Geology colleague Jack Larimer as well as the data from other LSPET researchers, helped Moore and his team understand the sources of lunar carbon. Specifically, they found that carbon from cosmic rays and solar wind is implanted into the lunar surface samples. The analyses of Apollo samples not only bolstered the reputation of the CMS as a research center, they also set the precedent for the study of all types of planetary materials by CMS researchers in the future.

Learn more about the Center for Meteorite Studies' history-making Apollo analyses here!

Watch an archived interview with Center Founding Director Prof Carleton B. Moore, here!

This post by Michelle Minitti originally appeared in the CMS newsletter, and is updated here.